After sharing some of our favorite wildlife in Glacier Bay National Park, today’s post is all about the ice.

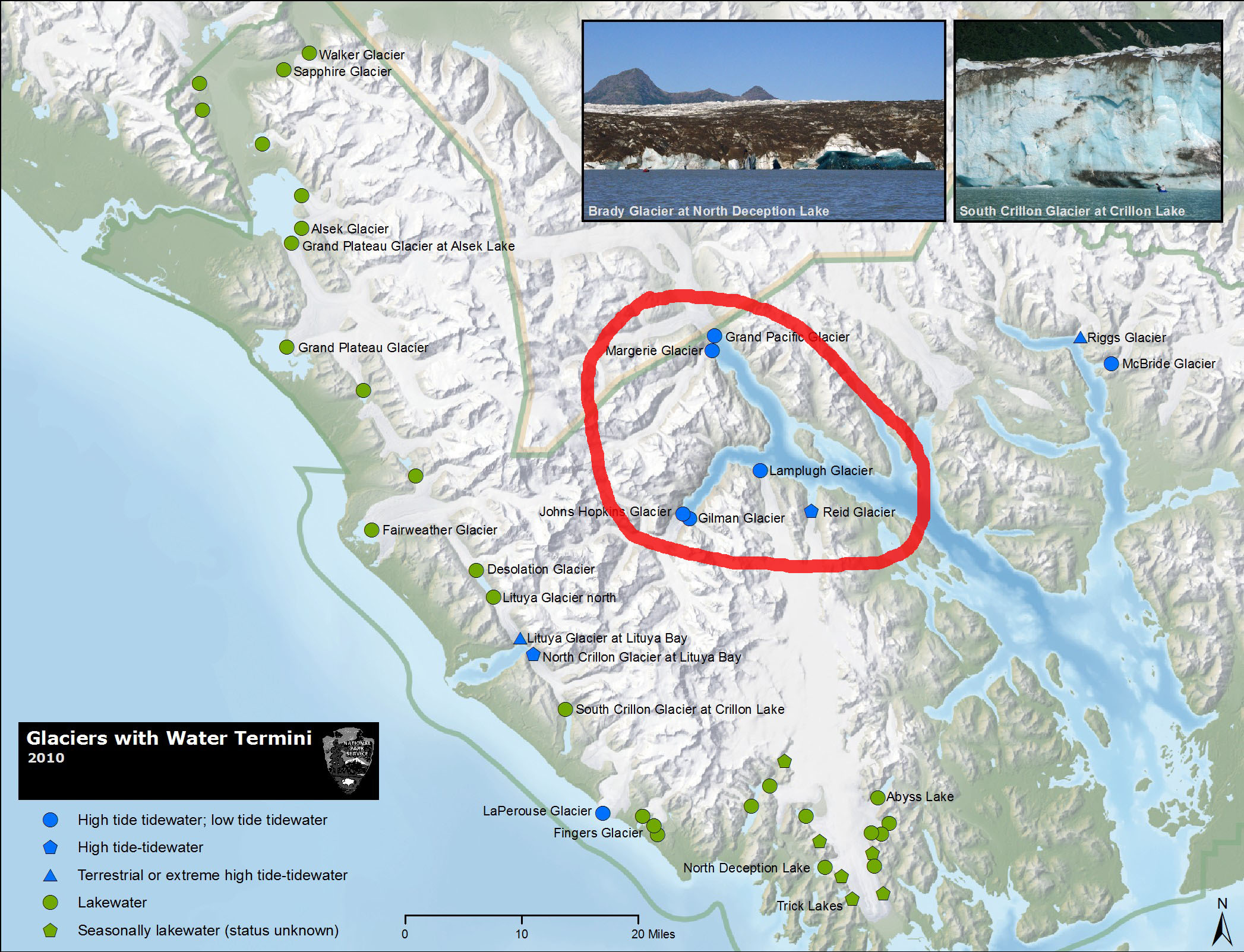

This map from the Park Service shows all the glaciers in the park that reach water – blue dots indicate salt water and green dots indicate fresh water lakes. The area circled in red is the west arm of the park that we explored this trip. There are hundreds of glaciers in the park that no longer reach water, called hanging glaciers like the Hoonah pictured here.

This map from the Park Service shows all the glaciers in the park that reach water – blue dots indicate salt water and green dots indicate fresh water lakes. The area circled in red is the west arm of the park that we explored this trip. There are hundreds of glaciers in the park that no longer reach water, called hanging glaciers like the Hoonah pictured here.

The first major glaciers we visited were the Margerie and Grand Pacific Glaciers – at the top of the red circle above. Note that the Grand Pacific glacier is now just across the border into Canada. The Margerie is the obvious glacier on the left, and the low dark gray area to the right is the grit-covered Grand Pacific. About 250 years ago, during the Little Ice Age, the Grand Pacific covered both the east and west arms of the park, all the way down to Icy Strait.

The Margerie is the obvious glacier on the left, and the low dark gray area to the right is the grit-covered Grand Pacific. About 250 years ago, during the Little Ice Age, the Grand Pacific covered both the east and west arms of the park, all the way down to Icy Strait. There’s something mesmerizing about the ice. Spires (called seracs) reach to the sky, chunks calve and fall into the water (or break off underwater and shoot to the surface), and the sound of cracking and rumbling remind us that the glacier is really a river of ice that’s constantly flowing down the mountains. As the mass of ice flows it picks up rocks, grinding and scouring the mountains underneath… embedding streaks of grit in the ice.

There’s something mesmerizing about the ice. Spires (called seracs) reach to the sky, chunks calve and fall into the water (or break off underwater and shoot to the surface), and the sound of cracking and rumbling remind us that the glacier is really a river of ice that’s constantly flowing down the mountains. As the mass of ice flows it picks up rocks, grinding and scouring the mountains underneath… embedding streaks of grit in the ice. Ice with air trapped in it looks white, but ice under pressure turns clear or even blue – an almost fake-looking turquoise color. The blue ice is so compressed that it absorbs all the colors of the spectrum except blue, which it reflects.

Ice with air trapped in it looks white, but ice under pressure turns clear or even blue – an almost fake-looking turquoise color. The blue ice is so compressed that it absorbs all the colors of the spectrum except blue, which it reflects. We think the most dramatic glacier in the bay is the Johns Hopkins glacier, and we were lucky that the inlet to it was pretty clear of ice so we were able to get fairly close. The grand view of it is what I love best though – with the rugged mountains behind.

We think the most dramatic glacier in the bay is the Johns Hopkins glacier, and we were lucky that the inlet to it was pretty clear of ice so we were able to get fairly close. The grand view of it is what I love best though – with the rugged mountains behind. It’s difficult to grasp the scale of these glaciers, as well as their age and their power. Standing before them, feeling the cold wind whipping down from the peaks where they begin, hearing their cracking and watching ice calve into the water only hints at what these glaciers are all about.

It’s difficult to grasp the scale of these glaciers, as well as their age and their power. Standing before them, feeling the cold wind whipping down from the peaks where they begin, hearing their cracking and watching ice calve into the water only hints at what these glaciers are all about.

Sometimes we can get to the side of a glacier and touch it or even climb on it, and that’s the case with the Reid Glacier. We can anchor in the basin that was formed by the Reid when it was larger, and take the dinghy to the shoreline near the face. This rushing river is melt water coming from underneath the glacier.

We can anchor in the basin that was formed by the Reid when it was larger, and take the dinghy to the shoreline near the face. This rushing river is melt water coming from underneath the glacier. By hiking along the water’s edge we can reach the side of the glacier and get a better view of the alien landscapes on top.

By hiking along the water’s edge we can reach the side of the glacier and get a better view of the alien landscapes on top.

Looking back towards the entrance to Reid Inlet you can really see how the glacier scoured the landscape, though some wildflowers and willow are beginning to establish themselves, paving the way for an eventual forest. We had a little uh-oh moment when we hiked back to the dinghy. Normally Jim is ridiculous about setting the dinghy anchor so high up on shore that it would take a Biblical flood to cover it. This time he mis-judged a bit…

We had a little uh-oh moment when we hiked back to the dinghy. Normally Jim is ridiculous about setting the dinghy anchor so high up on shore that it would take a Biblical flood to cover it. This time he mis-judged a bit… We had a good laugh about it, and the good news is that the tide was starting to fall so we wouldn’t have more than about an hour to wait… but it was also getting late in the day and we hadn’t had lunch yet! We suspected the anchor line was caught on a rock, but the opaque water made it impossible to guess where it was. There was another boat anchored near us, and it turns out that we have mutual boating friends. We spotted them out in their dinghy so we waved them over and they pulled up the anchor for us. Small world! But the little plover who had escorted us along the beach was not impressed.

We had a good laugh about it, and the good news is that the tide was starting to fall so we wouldn’t have more than about an hour to wait… but it was also getting late in the day and we hadn’t had lunch yet! We suspected the anchor line was caught on a rock, but the opaque water made it impossible to guess where it was. There was another boat anchored near us, and it turns out that we have mutual boating friends. We spotted them out in their dinghy so we waved them over and they pulled up the anchor for us. Small world! But the little plover who had escorted us along the beach was not impressed.

Great photos, Robin, as always, and I love the map! It is so hard for people to imagine if they haven’t actually BEEN THERE!!!!! Love the photo of the dinghy, too!